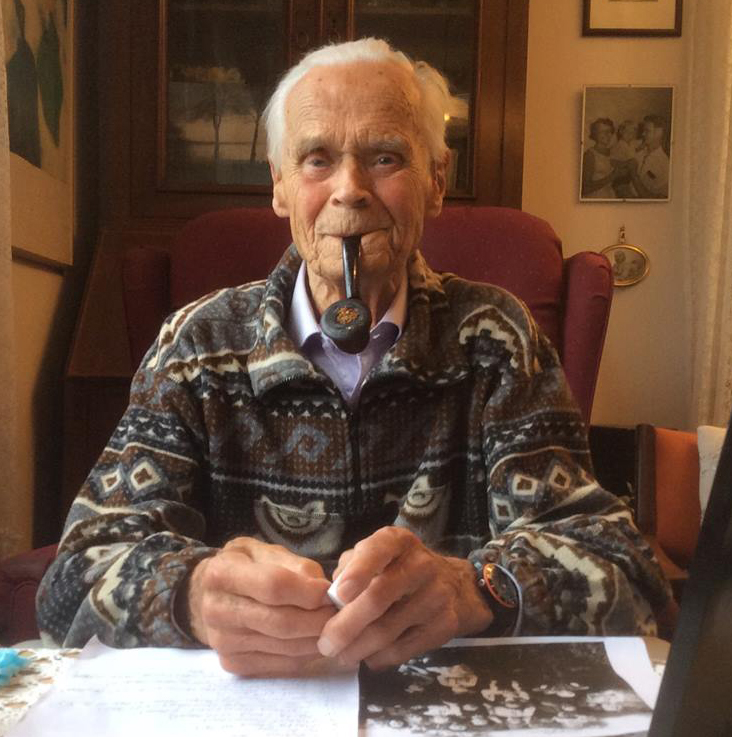

Ragnar Rommetveit (1924-2017)

26.06.2017, by Sibylle Classen in announcement

Obituary by Rolv Mikkel Blakar

Ragnar Rommetveit died June 11th, almost 93 years old. By Rommetveit’s death, the pioneers in European social psychology in the post war period and the founding fathers of the European Association of Social Psychology have all left us. Rommetveit was the last living member of the Planning Committee who prepared the first European Conference on Experimental Social Psychology held in Sorrento, December 12-16, 1963 and the second one held in Frascati, December 11-15, 1964. The other five members – John Lanzetta, chairman, Mauk Mulder, secretary, Robert Pagès, Henri Tajfel and John Thibaut – have all passed before.

From the perspective of Norwegian social psychology, Rommetveit’s contribution was two fold: Firstly, he was the one who in the post war years introduced modern, international (at that time mainly North American) social psychology into Norwegian social psychology. Secondly, he was the one who first placed an emerging Norwegian social psychology on the international map. Already his doctoral dissertation, published in 1955: “Social norms and roles” with the long and precise subtitle: “Explorations in the psychology of enduring social pressures with empirical contributions from inquiries into religious attitudes and sex roles of adolescents from some districts in western Norway” evoked broad international interest. A review of Norwegian social psychology prepared for the Committee on Transnational Social Psychology by Blakar & Nafstad on the invitation of Moscovici and published in European Journal of Social Psychology in 1982, demonstrates Rommetveit’s profound influence on an emerging social psychology in Norway and Europe.

From the perspective of European social psychology, his contribution was also two fold: On the one hand, he was as mentioned one of the founding fathers of EAESP (now EASP). Carl Grauman’s historical article on EASP’s homepage testifies to Rommetveit’s central role in this enterprise. Let me here add that Rommetveit, almost by nature, was rather hesitant to take on administrative duties as he prioritized to concentrate on academic work. The establishment and development of EASP as a counterweight to the North American dominance in social psychology was an exception in this respect. The establishment of EASP was formally passed in Leuven 1965. However, the “Organization for Comparative social Research” with the “Seven nations study” was in fact launched before and was according to Grauman’s historical review “designed in Oslo”.

Rommetveit had a strong influence in the early phase of EASP. Rommetveit also served as one of the teachers at the second Summer School in Leuven in 1967. Moreover, his group followed up their work from Leuven by a small group meeting in Oslo. This research work resulted in the very first volume (edited by Carswell & Rommetveit) in the new European Monographs series (edited by Tajfel). As Rommetveit’s student and assistant at that time, I had the pleasure to prepare the material for and assist in this small group meeting in Oslo. Thereby I learned how valuable the Summer School really is before I got the chance to participate myself in the Summer School in Konstanz in 1971.

Let me mention some highlights in Rommetveit’s academic production. Having been a visiting professor in the US meeting modern psycholinguistics, he published in 1968 “Words, Meanings and Messages” with the subtitle “Theory and Experiments in Psycholinguistics” – Rommetveit’s own critical introduction to the psychology of language and communication.

In 1974 he published another strong contribution: “On message structure” with the subtitle “a framework for the study of language and communication” in which he explicated his dialogical approach and his understanding of how intersubjectivity is constructed. In this book Rommetveit challenged the foundation of the so called Harvard MIT School of linguistics dominating the field at that time. However, dialogue between Rommetveit’s relatively critical European perspectives and predominant American perspectives were not easy, and a positive American review in Contemporary Psychology concluded about Rommetveit’s theoretical perspective that “the message will not get through”. Given more than forty years of hindsight, we can conclude that to day Rommetveit’s communication perspective on language is, if not mainstream, at least much more widely accepted.

Working in a highly interdisciplinary field, Rommetveit’s empirical works were typically scattered in a variety of different journals, not easy to track down for those interested. Therefore in 1979 the volume “Studies of Language, Thought, and Verbal Communication”, edited by Rommetveit & Blakar, compiling two decades of productive empirical work, was published to make Rommetveit and colleagues’ studies and publications easier available.

In his chapter in the volume “The Dialogical Alternative”, edited by Astri Heen Wold in 1992, Rommetveit summarized the essentials of a social cognitive and dialogical approach into a set of general statements about human cognition and communication. Here he summarized his theoretical position in terms of a series of (24) presuppositions about the social nature of the human being formulated in an explicitly axiomatic form.

Norway is a small country in the periphery of the world and Oslo is far from being a metropole attracting interesting people from everywhere. Nevertheless, as a student in psychology 1965-70 I got a strong feeling that Oslo was one of the leading centers of social psychology in Europe – together with Bristol (Henri Tajfel) and Paris (Serge Moscovici). For within social psychology and the psychology of language and communication in particular we continuously had scholars visiting us presenting enriching lectures, and just as important, students staying with us for shorter or longer periods to get to know the psychology taught here. All this was due to one single person: Ragnar Rommetveit.